Collatz conjecture

| Does the Collatz sequence from initial value n eventually reach 1, for all n > 0? |

The Collatz conjecture is a conjecture in mathematics named after Lothar Collatz, who first proposed it in 1937. The conjecture is also known as the 3n + 1 conjecture, the Ulam conjecture (after Stanisław Ulam), Kakutani's problem (after Shizuo Kakutani), the Thwaites conjecture (after Sir Bryan Thwaites), Hasse's algorithm (after Helmut Hasse), or the Syracuse problem;[1] the sequence of numbers involved is referred to as the hailstone sequence or hailstone numbers,[2] or as wondrous numbers.[3]

Take any natural number n. If n is even, divide it by 2 to get n / 2. If n is odd, multiply it by 3 and add 1 to obtain 3n + 1. Repeat the process (which has been called "Half Or Triple Plus One", or HOTPO[4]) indefinitely. The conjecture is that no matter what number you start with, you will always eventually reach 1. The property has also been called oneness.[5]

Paul Erdős said, allegedly, about the Collatz conjecture: "Mathematics is not yet ripe for such problems"[6] and also offered $500 for its solution.[7]

In 2007, researchers Kurtz and Simon, building on earlier work by J.H. Conway in the 1970s,[8] proved that a natural generalization of the Collatz problem is algorithmically undecidable.[7]

However, this proof just says that existence of a general formula or algorithm that would work for every value of n in every subset of the generalized collatz problem is undecidable .

Contents |

Statement of the problem

Consider the following operation on an arbitrary positive integer:

- If the number is even, divide it by two.

- If the number is odd, triple it and add one.

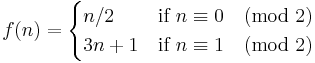

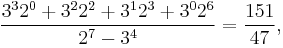

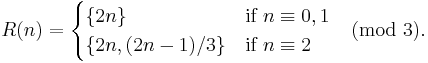

In modular arithmetic notation, define the function f as follows:

Now, form a sequence by performing this operation repeatedly, beginning with any positive integer, and taking the result at each step as the input at the next.

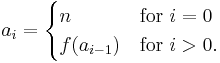

In notation:

(that is:  is the value of

is the value of  applied to

applied to  recursively

recursively  times;

times;  )

)

or

(which yields  for even

for even  and

and  for odd

for odd  ).

).

The Collatz conjecture is: This process will eventually reach the number 1, regardless of which positive integer is chosen initially.

That smallest i such that ai = 1 is called the total stopping time of n.[9] The conjecture asserts that every n has a well-defined total stopping time. If, for some n, such an i doesn't exist, we say that n has infinite total stopping time and the conjecture is false.

If the conjecture is false, it can only be because there is some starting number which gives rise to a sequence which does not contain 1. Such a sequence might enter a repeating cycle that excludes 1, or increase without bound. No such sequence has been found.

Examples

For instance, starting with n = 6, one gets the sequence 6, 3, 10, 5, 16, 8, 4, 2, 1.

n = 11, for example, takes longer to reach 1: 11, 34, 17, 52, 26, 13, 40, 20, 10, 5, 16, 8, 4, 2, 1.

The sequence for n = 27, listed and graphed below, takes 111 steps, climbing to over 9000 before descending to 1.

- { 27, 82, 41, 124, 62, 31, 94, 47, 142, 71, 214, 107, 322, 161, 484, 242, 121, 364, 182, 91, 274, 137, 412, 206, 103, 310, 155, 466, 233, 700, 350, 175, 526, 263, 790, 395, 1186, 593, 1780, 890, 445, 1336, 668, 334, 167, 502, 251, 754, 377, 1132, 566, 283, 850, 425, 1276, 638, 319, 958, 479, 1438, 719, 2158, 1079, 3238, 1619, 4858, 2429, 7288, 3644, 1822, 911, 2734, 1367, 4102, 2051, 6154, 3077, 9232, 4616, 2308, 1154, 577, 1732, 866, 433, 1300, 650, 325, 976, 488, 244, 122, 61, 184, 92, 46, 23, 70, 35, 106, 53, 160, 80, 40, 20, 10, 5, 16, 8, 4, 2, 1 }

Numbers with a total stopping time longer than any smaller starting value form a sequence beginning with:

- 1, 2, 3, 6, 7, 9, 18, 25, 27, 54, 73, 97, … (sequence A006877 in OEIS).

The record holder for total stopping time for numbers less than 100 million is 63,728,127, with 949 steps, for numbers less than 1 billion it is 670,617,279, with 986 steps, and for numbers less than 10 billion it is 9,780,657,630, with 1132 steps.,[10][11]

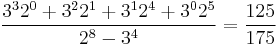

The powers of two converge to one quickly because  is halved

is halved  times to reach one, and is never increased.

times to reach one, and is never increased.

Program to calculate Hailstone sequences

A specific Hailstone sequence can be easily computed, as is shown by this pseudocode example:

- function hailstone(n)

- while n > 1

- show n

- if n is odd then

- set n = 3n + 1

- else

- set n = n / 2

- endif

- endwhile

- show n

- while n > 1

This program halts when the sequence reaches 1, in order to avoid printing an endless cycle of 4, 2, 1. If the Collatz conjecture is true, the program will always halt (stop) no matter what positive starting integer is given to it.

m-cycles cannot occur

The conjecture could be proven, indirectly, as a consequence of the following:

- no infinite divergent trajectory occurs

- no cycle occurs

These being true, all natural numbers would have a trajectory down to one.

In 1977, R. Steiner, and in 2000 and 2002, J. Simons and B. de Weger (based on Steiner's work), proved the nonexistence of certain types of cycles.

Notation

To explain this we refer to the definition as given in the section Syracuse function below:

Define the transformation for odd positive integer numbers a and b, positive integer numbers A:

- b = T(a;A) meaning b = (3a + 1)/2A

where A has the maximum value which leaves b an integer.

- Example:

- a = 7. Then b = T(7, A) and 3a + 1 = 22,

- so A = 1

- b = (3×7 + 1)/21 = 11

- 11 = T(7;1)

Define the concatenation (extensible up to arbitrary length):

- b = T(T(a;A);B) = T(a;A,B)

- Example:

b = T(7; A, B) = T(7;1,1) = ((3×7 + 1)/21×3 + 1)/2B = (3×11 + 1)/2B = 34/21 = 17

- 17 = T(7;1,1)

Define a "one-peak-transformation" of L ascending and 1 descending exponents/steps:

- b = T(a;1,1,1,1,1,....,1,A) = T(a;(1)L,A)

with L (arbitrary) many exponents 1 and exactly one exponent A > 1

- Example:

- b = T(7;1,1,A) = T(7;(1)2, A) = (17×3 + 1)/2A = 52/22 = 13

- 13 = T(7;(1)2,2)

then call the construction

a = T(a; (1)L,A) // arbitrary positive value for number of increasing steps L

a "1-cycle" of length N = L + 1 (steps).

Theorems

- Steiner proved in 1977 there is no 1-cycle. However many L steps may be chosen, a number x satisfying the loop-condition is never an integer.

- Simons proved in 2000 (based on Steiner's method) there is no 2-cycle a = T(a;(1)L,A,(1)M,B) however many L and M steps may be chosen.

- Simons/deWeger in 2003 extended their own proof up to "68-cycles": there is no m-cycle up to m = 68 a = T(a;(1)L1,A1,(1)L2,A2,...,(1)L68,A68). Whatever number of steps in L1 to L68 and whatever exponents A1 to A68 one may choose, there is no positive odd integer number a satisfying the cycle condition. Steiner claimed in a usenet discussion he could extend this up to m = 71.[12]

-

- Comment: These theorems were derived by results of the theory of rational approximation of transcendental numbers. Simons/deWeger concluded their article with the comment, that this method of approximation is exhausted with that results, and a completely different approach is needed to be able to proceed qualitatively.

Supporting arguments

Although the conjecture has not been proven, most mathematicians who have looked into the problem think the conjecture is true because experimental evidence and heuristic arguments support it.

Experimental evidence

The conjecture has been checked by computer for all starting values up to 20 × 258 ≈ 5.764×1018.[13] All initial values tested so far eventually end in the repeating cycle {4,2,1}, which has only three terms. It is also known that {4,2,1} is the only repeating cycle possible with fewer than 35400 terms.[14]

Such computer evidence is not a proof that the conjecture is true. As shown in the cases of the Pólya conjecture, the Mertens conjecture and the Skewes' number, sometimes a conjecture's only counterexamples are found when using very large numbers. Since sequentially examining all natural numbers is a process which can never be completed, such an approach can never demonstrate that the conjecture is true, merely that no counterexamples have yet been discovered.

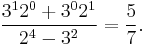

A probabilistic heuristic

If one considers only the odd numbers in the sequence generated by the Collatz process, then each odd number is on average 3/4 of the previous one.[15] (More precisely, the geometric mean of the ratios of outcomes is 3/4.) This yields a heuristic argument that every Hailstone sequence should decrease in the long run, although this is not evidence against other cycles, only against divergence. The argument is not a proof because it assumes that Hailstone sequences are assembled from uncorrelated probabilistic events. (It does rigorously establish that the 2-adic extension of the Collatz process has two division steps for every multiplication step for almost all 2-adic starting values.)

Rigorous bounds

Although it is not known rigorously whether all positive numbers eventually reach one according to the Collatz iteration, it is known that many numbers do so. In particular, Krasikov and Lagarias showed that the number of integers in the interval [1,x] that eventually reach one is at least proportional to x0.84.[16]

Other formulations of the conjecture

In reverse

There is another approach to prove the conjecture, which considers the bottom-up method of growing the so called Collatz graph. The Collatz graph is a graph defined by the inverse relation

So, instead of proving that all natural numbers eventually lead to 1, we can prove that 1 leads to all natural numbers. For any integer n, n ≡ 1 (mod 2) iff 3n + 1 ≡ 4 (mod 6). Equivalently, (n − 1)/3 ≡ 1 (mod 2) iff n ≡ 4 (mod 6). Conjecturally, this inverse relation forms a tree except for the 1–2–4 loop (the inverse of the 1–4–2 loop of the unaltered function f defined in the statement of the problem above). When the relation 3n + 1 of the function f is replaced by the common substitute "shortcut" relation (3n + 1)/2, the Collatz graph is defined by the inverse relation,

Conjecturally, this inverse relation forms a tree except for a 1–2 loop (the inverse of the 1–2 loop of the function f(n) revised as indicated above).

As an abstract machine that computes in base two

Repeated applications of the Collatz function can be represented as an abstract machine that handles strings of bits. The machine will perform the following three steps on any odd number until only one "1" remains:

- Append 1 to the (right) end of the number in binary (giving 2n + 1);

- Add this to the original number by binary addition (giving 2n + 1 + n = 3n + 1);

- Remove all trailing "0"s (i.e. repeatedly divide by two until the result is odd).

This prescription is plainly equivalent to computing a Hailstone sequence in base two.

Example

The starting number 7 is written in base two as 111. The resulting Hailstone sequence is:

111

1111

10110

10111

100010

100011

110100

11011

101000

1011

10000

As a parity sequence

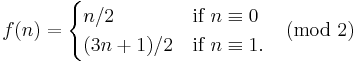

For this section, consider the Collatz function in the slightly modified form

This can be done because when n is odd, 3n + 1 is always even.

If P(…) is the parity of a number, that is P(2n) = 0 and P(2n + 1) = 1, then we can define the Hailstone parity sequence for a number n as pi = P(ai), where a0 = n, and ai+1 = f(ai).

Using this form for f(n), it can be shown that the parity sequences for two numbers m and n will agree in the first k terms if and only if m and n are equivalent modulo 2k. This implies that every number is uniquely identified by its parity sequence, and moreover that if there are multiple Hailstone cycles, then their corresponding parity cycles must be different.

The proof is simple: it is easy to verify by hand that applying the f function k times to the number a·2k + b will give the result a·3c + d, where d is the result of applying the f function k times to b, and c is how many odd numbers were encountered during that sequence. So the parity of the first k numbers is determined purely by b, and the parity of the (k + 1)th number will change if the least significant bit of a is changed.

The Collatz Conjecture can be rephrased as stating that the Hailstone parity sequence for every number eventually enters the cycle 0 → 1 → 0.

As a tag system

For the Collatz function in the form

Hailstone sequences can be computed by the extremely simple 2-tag system with production rules a → bc, b → a, c → aaa. In this system, the positive integer n is represented by a string of n a's, and iteration of the tag operation halts on any word of length less than 2. (Adapted from De Mol.)

The Collatz conjecture equivalently states that this tag system, with an arbitrary finite string of a's as the initial word, eventually halts (see Example: Computation of Collatz sequences for a worked example).

Extensions to larger domains

Iterating on all integers

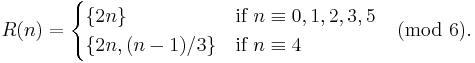

An obvious extension is to include all integers, not just positive integers. In this case there are a total of 5 known cycles, which all integers seem to eventually fall into under iteration of f. These cycles are listed here, starting with the well-known cycle for positive n.

Odd values are listed in bold. Each cycle is listed with its member of least absolute value (which is always odd or zero) first.

| Cycle | Odd-value cycle length | Full cycle length |

|---|---|---|

| 1 → 4 → 2 → 1 … | 1 | 3 |

| 0 → 0 … | 0 | 1 |

| −1 → −2 → −1 … | 1 | 2 |

| −5 → −14 → −7 → −20 → −10 → −5 … | 2 | 5 |

| −17 → −50 → −25 → −74 → −37 → −110 → −55 → −164 → −82 → −41 → −122 → −61 → −182 → −91 → −272 → −136 → −68 → −34 → −17 … | 7 | 18 |

The Generalized Collatz Conjecture is the assertion that every integer, under iteration by f, eventually falls into one of these five cycles.

Iterating with odd denominators or 2-adic integers

The standard Collatz map can be extended to (positive or negative) rational numbers which have odd denominators when written in lowest terms. The number is taken to be odd or even according to whether its numerator is odd or even. A closely related fact is that the Collatz map extends to the ring of 2-adic integers, which contains the ring of rationals with odd denominators as a subring.

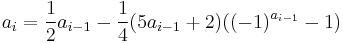

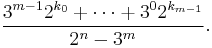

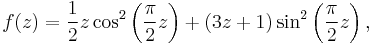

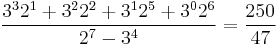

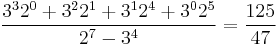

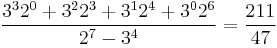

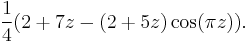

The parity sequences as defined above are no longer unique for fractions. However, it can be shown that any possible parity cycle is the parity sequence for exactly one fraction: if a cycle has length n and includes odd numbers exactly m times at indices k0, …, km−1, then the unique fraction which generates that parity cycle is

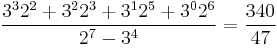

For example, the parity cycle (1 0 1 1 0 0 1) has length 7 and has 4 odd numbers at indices 0, 2, 3, and 6. The unique fraction which generates that parity cycle is

the complete cycle being: 151/47 → 250/47 → 125/47 → 211/47 → 340/47 → 170/47 → 85/47 → 151/47

Although the cyclic permutations of the original parity sequence are unique fractions, the cycle is not unique, each permutation's fraction being the next number in the loop cycle:

- (0 1 1 0 0 1 1) →

- (1 1 0 0 1 1 0) →

- (1 0 0 1 1 0 1) →

- (0 0 1 1 0 1 1) →

- (0 1 1 0 1 1 0) →

- (1 1 0 1 1 0 0) →

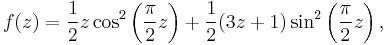

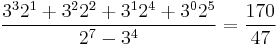

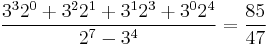

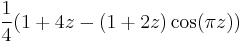

Also, for uniqueness, the parity sequence should be "prime", i.e., not partitionable into identical sub-sequences. For example, parity sequence (1 1 0 0 1 1 0 0) can be partitioned into two identical sub-sequences (1 1 0 0)(1 1 0 0). Calculating the 8-element sequence fraction gives

- (1 1 0 0 1 1 0 0) →

But when reduced to lowest terms {5/7}, it is the same as that of the 4-element sub-sequence

- (1 1 0 0) →

And this is because the 8-element parity sequence actually represents two circuits of the loop cycle defined by the 4-element parity sequence.

In this context, the Collatz conjecture is equivalent to saying that (0 1) is the only cycle which is generated by positive whole numbers (i.e. 1 and 2).

Iterating on real or complex numbers

The Collatz map can be viewed as the restriction to the integers of the smooth real and complex map

which simplifies to

If the standard Collatz map defined above is optimized by replacing the relation 3n + 1 with the common substitute "shortcut" relation (3n + 1)/2, it can be viewed as the restriction to the integers of the smooth real and complex map

which simplifies to  .

.

Collatz fractal

Iterating the above optimized map in the complex plane produces the Collatz fractal.

The point of view of iteration on the real line was investigated by Chamberland (1996), and on the complex plane by Letherman, Schleicher, and Wood (1999).

Optimizations

The As a parity sequence section above gives a way to speed up simulation of the sequence. To jump ahead k steps on each iteration (using the f function from that section), break up the current number into two parts, b (the k least significant bits, interpreted as an integer), and a (the rest of the bits as an integer). The result of jumping ahead k steps can be found as:

- f k(a 2k + b) = a 3c(b) + d(b).

The c and d arrays are precalculated for all possible k-bit numbers b, where d(b) is the result of applying the f function k times to b, and c(b) is the number of odd numbers encountered on the way. For example, if k=5, you can jump ahead 5 steps on each iteration by separating out the 5 least significant bits of a number and using:

- c(0..31) = {0,3,2,2,2,2,2,4,1,4,1,3,2,2,3,4,1,2,3,3,1,1,3,3,2,3,2,4,3,3,4,5}

- d(0..31) = {0,2,1,1,2,2,2,20,1,26,1,10,4,4,13,40,2,5,17,17,2,2,20,20,8,22,8,71,26,26,80,242}.

This requires 2k precomputation and storage to speed up the resulting calculation by a factor of k, a space-time tradeoff.

For the special purpose of searching for a counterexample to the Collatz conjecture, this precomputation leads to an even more important acceleration due to Tomás Oliveira e Silva and is used in the record confirmation of the Collatz conjecture. If, for some given b and k, the inequality

- f k(a 2k + b) = a 3c(b) + d(b) < a 2k + b

holds for all a, then the first counterexample, if it exists, cannot be b modulo 2k. For instance, the first counterexample must be odd because f(2n) = n; and it must be 3 mod 4 because f3(4n + 1) = 3n + 1. For each starting value a which is not a counterexample to the Collatz conjecture, there is a k for which such an inequality holds, so checking the Collatz conjecture for one starting value is as good as checking an entire congruence class. As k increases, the search only needs to check those residues b that are not eliminated by lower values of k. On the order of 3k/2 residues survive. For example, the only surviving residues mod 32 are 7, 15, 27, and 31; only 573,162 residues survive mod 225 = 33,554,432.

Syracuse function

If k is an odd integer, then 3k + 1 is even, so we can write 3k + 1 = 2ak′, with k' odd and a ≥ 1. We define a function f from the set  of odd integers into itself, called the Syracuse function, by taking f (k) = k′ (sequence A075677 in OEIS).

of odd integers into itself, called the Syracuse function, by taking f (k) = k′ (sequence A075677 in OEIS).

Some properties of the Syracuse function are:

- f (4k + 1) = f (k) for all k in

.

. - For all p ≥ 2 and h odd, fp−1(2p h − 1) = 2·3p − 1h − 1 (here, f p−1 is function iteration notation).

- For all odd h, f(2h − 1) ≤ (3h − 1)/2

The Syracuse conjecture is that for all k in  , there exists an integer n ≥ 1 such that fn(k) = 1. Equivalently, let E be the set of odd integers k for which there exists an integer n ≥ 1 such that fn(k) = 1. The problem is to show that E =

, there exists an integer n ≥ 1 such that fn(k) = 1. Equivalently, let E be the set of odd integers k for which there exists an integer n ≥ 1 such that fn(k) = 1. The problem is to show that E =  . The following is the beginning of an attempt at a proof by induction:

. The following is the beginning of an attempt at a proof by induction:

1, 3, 5, 7, and 9 are known to be elements of E. Let k be an odd integer greater than 9. Suppose that the odd numbers up to and including k − 2 are in E and let us try to prove that k is in E. As k is odd, k + 1 is even, so we can write k + 1 = 2ph for p ≥ 1, h odd, and k = 2ph − 1. Now we have:

- If p = 1, then k = 2h − 1. It is easy to check that f (k) < k , so f (k) ∈ E; hence k ∈ E.

- If p ≥ 2 and h is a multiple of 3, we can write h = 3h′. Let k′ = 2p + 1h′ − 1; then f (k′) = k , and as k′ < k , k′ is in E; therefore k = f (k′) ∈ E.

- If p ≥ 2 and h is not a multiple of 3 but h ≡ (−1)p mod 4, we can still show that k ∈ E.

The problematic case is that where p ≥ 2 , h not multiple of 3 and h ≡ (−1)p + 1 mod 4. Here, if we manage to show that for every odd integer k′, 1 ≤ k′ ≤ k − 2 ; 3k′ ∈ E we are done.

See also

Notes

- ^ Maddux, Cleborne D.; Johnson, D. Lamont (1997). Logo: A Retrospective. New York: Haworth Press. p. 160. ISBN 0789003740. "The problem is also known by several other names, including: Ulam's conjecture, the Hailstone problem, the Syracuse problem, Kakutani's problem, Hasse's algorithm, and the Collatz problem."

- ^ Pickover, Clifford A. (2001). Wonders of Numbers. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 116–118. ISBN 0195133420.

- ^ Hofstadter, Douglas R. (1979). Gödel, Escher, Bach. New York: Basic Books. pp. 400–402. ISBN 0465026850.

- ^ Friendly, Michael (1988). Advanced Logo: A Language for Learning. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. ISBN 0898599334.

- ^ Paul Bourke (December 1992). "Decision Procedure for "Oneness"". University of West Alabama. http://local.wasp.uwa.edu.au/~pbourke/fractals/oneness/.

- ^ R. K. Guy: Don't try to solve these problems, Amer. Math. Monthly, 90(1983), 35–41.

- ^ a b Kurtz, Stuart A.; Simon, Janos (2007). "The Undecidability of the. Generalized Collatz Problem". In Cai, J.-Y.; Cooper, S.B.; Zhu, H. By this Erdos means that there aren't powerfull tools for manipulating such objects.. Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Theory and Applications of Models of Computation, TAMC 2007, held in Shanghai, China in May 2007. pp. 542–553. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-72504-6_49. ISBN 3540725032. http://books.google.com/books?id=mhrOkx-xyJIC&pg=PA542. Also available here: http://www.cs.uchicago.edu/~simon/RES/collatz.pdf

- ^ "J. H. Conway proved the remarkable result that a simple generalization of the problem is algorithmically undecidable." Quoting Lagarias 1985:

- ^ * Jeffrey C. Lagarias (January 1985). "The 3x + 1 problem and its generalizations". American Mathematical Monthly 92 (1): 3–23. doi:10.2307/2322189. JSTOR 2322189.

- ^ Leavens, Gary T.; Vermeulen, Mike (December 1992). "3x+1 Search Programs". Computers & Mathematics with Applications 24 (11): 79–99. doi:10.1016/0898-1221(92)90034-F.

- ^ Roosendaal, Eric. "3x+1 Delay Records". http://www.ericr.nl/wondrous/delrecs.html. Retrieved 27 November 2011. (Note: "Delay records" are total stopping time records.)

- ^ http://groups.google.com/group/sci.math/msg/1ed7cd277079efdd

- ^ Silva, Tomás Oliveira e Silva. "Computational verification of the 3x+1 conjecture". http://www.ieeta.pt/~tos/3x+1.html. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ^ Garner, Lynn E. (1981). "On the Collatz 3n + 1 Algorithm". Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society 82 (1): 19–22. doi:10.2307/2044308. JSTOR 2044308.

- ^ http://www.cecm.sfu.ca/organics/papers/lagarias/paper/html/node3.html

- ^ Krasikov, Ilia; Lagarias, Jeffrey C. (2003). "Bounds for the 3x + 1 problem using difference inequalities". Acta Arithmetica 109 (3): 237–258. doi:10.4064/aa109-3-4. MR1980260.

References and external links

Papers

- Jeffrey C. Lagarias (2006). "The 3x + 1 problem: An annotated bibliography, II (2000–)". arXiv:math.NT/0608208 [math.NT].

- Jeffrey C. Lagarias (2001), "Syracuse problem", in Hazewinkel, Michiel, Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1556080104, http://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=S/s110330

- Günther J. Wirsching. The Dynamical System Generated by the

Function. Number 1681 in Lecture Notes in Mathematics. Springer-Verlag, 1998.

Function. Number 1681 in Lecture Notes in Mathematics. Springer-Verlag, 1998. - Keith Matthews' 3x + 1 page: Review of progress, plus various programs

- Marc Chamberland. A continuous extension of the 3x + 1 problem to the real line. Dynam. Contin. Discrete Impuls Systems 2:4 (1996), 495–509.

- Simon Letherman, Dierk Schleicher, and Reg Wood: The (3n + 1)-Problem and Holomorphic Dynamics. Experimental Mathematics 8:3 (1999), 241–252.

- Ohira, Reiko & Yamashita, Michinori A generalization of the Collatz problem (Japanese)

- Urata, Toshio Some Holomorphic Functions connected with the Collatz Problem

- Matti K. Sinisalo: On the minimal cycle lengths of the Collatz sequences, Preprint, June 2003, University of Oulu

- Paul Stadfeld: Blueprint for Failure: How to Construct a Counterexample to the Collatz Conjecture

- De Mol, Liesbeth, "Tag systems and Collatz-like functions", Theoretical Computer Science, 390:1, 92–101, January 2008 (Preprint Nr. 314).

- Bruschi, Mario (2008). "A generalization of the Collatz problem and conjecture". arXiv:0810.5169 [math.NT].

- Andrei, Stefan; Masalagiu, Cristian (1998). "About the Collatz conjecture". Acta Informatica 35 (2): 167. doi:10.1007/s002360050117.

- Van Bendegem, Jean Paul, "The Collatz Conjecture: A Case Study in Mathematical Problem Solving", Logic and Logical Philosophy, Volume 14 (2005), 7–23

- Belaga, Edward G., "Reflecting on the 3x+1 Mystery", University of Strasbourg preprint, 1998.

- Belaga, Edward G.; Mignotte, Maurice, "Walking Cautiously into the Collatz Wilderness: Algorithmically, Number Theoretically, Randomly", Fourth Colloquium on Mathematics and Computer Science : Algorithms, Trees, Combinatorics and Probabilities, September 18–22, 2006, Institut Élie Cartan, Nancy, France

- Belaga, Edward G.; Mignotte, Maurice, "Embedding the 3x+1 Conjecture in a 3x+d Context", Experimental Mathematics, Volume 7, issue 2, 1998.

- Steiner, R.P.; "A theorem on the syracuse problem", Proceedings of the 7th Manitoba Conference on Numerical Mathematics,pages 553–559, 1977.

- Simons,J.;de Weger, B.; "Theoretical and computational bounds for m-cycles of the 3n + 1 problem", Acta Arithmetica, (online version 1.0, November 18, 2003), 2005.

Books

- Guy, Richard K., Unsolved problems in Number Theory, Springer, 2004. ISBN 0387208607. Cf. pp.336–337, "E17: Permutation Sequences" and the Collatz Conjecture.

General

- Distributed Computing project that verifies the Collatz conjecture for larger values.

- An ongoing distributed computing project by Eric Roosendaal verifies the Collatz conjecture for larger and larger values.

- Another ongoing distributed computing project by Tomás Oliveira e Silva continues to verify the Collatz conjecture (with fewer statistics than Eric Roosendaal's page but with further progress made).

- An animated implementation that uses arbitrary-precision arithmetic.

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Collatz Problem" from MathWorld.

- Collatz Problem at PlanetMath.

- Hailstone Patterns discusses different resonators along with using important numbers in the problem (like 6 and 3^5) to discover patterns.

- Collatz Iterations on the Ulam Spiral grid on YouTube

- Collatz Paths by Jesse Nochella, Wolfram Demonstrations Project.

- Page allowing to study and to show the guess for a given number

- Collatz cycles? about cycles, very basic, contains also some unusual graphs(html)

- Collatz cycles? (pdf) about loops, compacted text, rather basic (pdf)

- Collatz sequence for any number up to 500 digits in length.